Tutorial: RFID feeders to Networks

updated 10/21/24

Setup

Download the data folder, Create working directory, & start an R script

You will also need the sample data. This involves a whole folder. Here is a simple way to download the sample data folder you need:

Paste this url into the bar: https://github.com/dshizuka/networkanalysis/tree/gh-pages/SampleData/RFIDdata_for_download

Unzip and rename the folder as “RFID_sample_data”. *Don’t skip this step! If the folder is not named correctly, the codes won’t work!!**

Put the folder in your working directory. If you don’t know how to make a working directory, I recommend using Rstudio projects. Here is a brief step-by-step:

Create a folder somewhere on your computer and call it something like “RFID_tutorial”

Move the “RFID_sample_data” folder into the “RFID_tutorial” folder you just created.

Open RStudio

Go to File > New Project > Existing Directory

Click “Browse” and find the “RFID_tutorial” folder you just created. Click “Create Project”. This will open a new Rstudio window.

Go to File > New File > R Script. This will create a new R script file. You can then start copying & pasting the code chunks from this tutorial.

Whenever you want to come back to the R script, make sure to start by opening the .rproj file. This will make sure that the working directory is always the folder that this .rproj file is in.

Load necessary packages

Now let’s load the R packages that will be necessary for the tutorial:

library(dplyr)

library(tidyr)

library(lubridate)

library(asnipe)

library(igraph)Intro

There are lots of ways to set up an RFID detection array. RFID is powerful because it can generate very high-resolution data on visitation to a location by individuals. RFID systems can collect data 24 hours, 7 days a week–as long as the battery lasts (which is a key point).

The main limitation of RFID systems is that the detection area is very small–on the order of centimeters from the antenna. For this reason, RFID systems work best when you can set up antennas at a very restricted location where an animal will reliably be detected–e.g., a perch in front of the port of a feeder, an entry point into a nest box or burrow, etc.

There are some great resources for general information about RFID systems. Here are a few:

1.Bridge ES. An Arduino-Based RFID Platform for Animal Research. (2019) Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. 2019;7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2019.00257

2.Bonter DN, Bridge ES. (2011) Applications of radio frequency identification (RFID) in ornithological research: a review. Journal of Field Ornithology;82(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1557-9263.2010.00302.x

3.Smith JE, Pinter-Wollman N. (2021) Observing the unwatchable: Integrating automated sensing, naturalistic observations and animal social network analysis in the age of big data. Journal of Animal Ecology;90(1):62–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.13362

Great applications of RFID systems for animal behavior research is coming out all the time!

In this tutorial, I use data from the Arduino-based RFID platform as described in Bridge et al. (2019) cited above.

Notes on the Field Protocol

Some key things to think about when deploying an RFID system:

Swipe a test tag when you deploy your unit, and right before you collect the data. Keep the tag ID and the times you swipe the tag in your notes. First of all, this will allow you to know whether the unit has properly deployed and operational, and that the antenna is connected. This will allow you to double-check that your date and time data are correct. This is important because there are many reasons that your data and time can get out of sync with real time: e.g., temporary battery failure (this is especially common in very cold temperature), programming error. Moreover, the clock on your board can simply drift over time–usually just a few seconds across weeks, but it’s something you’ll want to keep track of.

Think about how to name your board and your data. Will the same board be assigned to the same feeder/box/location for the entirety of the season? If so, then you can go ahead and name the board with the name of the feeder. However, I have found that I sometimes have to swap out boards if something fails, or if I decide to change up which feeders are going to be used, etc. If so, then I would name the board with a unique ID, and then rename the data files with the feeder name.

Try to replace your battery before they run out. The Arduino program logs when the board turns on. On the other hand, if the battery dies, it just dies and you do not know when it stopped. So it’s a good idea to run a lot of pilot trials and see how long your battery pack lasts in different conditions so that you can predict how long they will last and do your best to replace the power before it runs out.

The overall pipeline

Here is the general pipeline:

Check the data

Compile data across multiple sensors

Cross-reference RFID data with individual attributes

Detect “gathering events” using Gaussian Mixture Models

Calculate association index and construct network

1. Dealing with the raw data

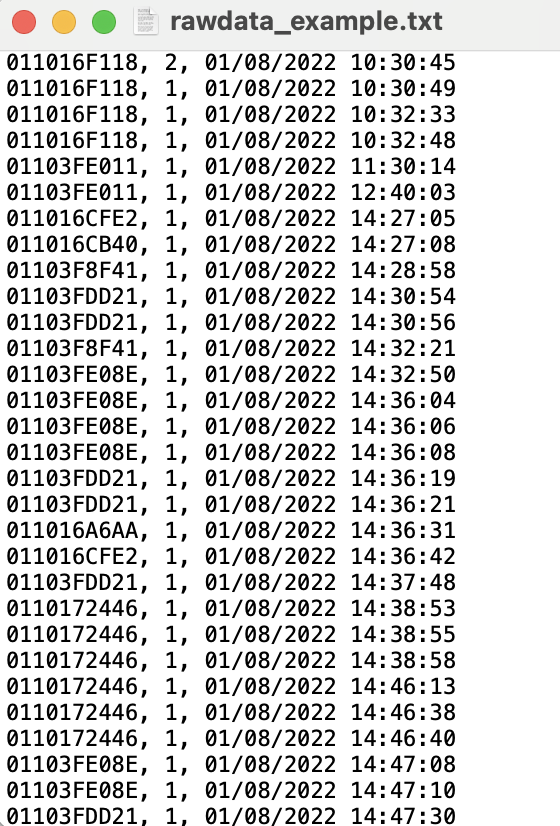

Your raw data from a data logger will look something like this.

There are three columns separated by a comma. The columns are:

RFID of the tag that was scanned.

The antenna that tag was scanned on. It can be “1” or “2” depending on how many and which antenna connections are used.

Date and time when the tag was scanned. Note that this is in the format of month/date/year

hour:minute:second, all in one column.

This is what it looks like when you import the file into R:

1.1. Data check & prep before compiling data from all sensors.

There are a few things to be aware of prior to importing the data into R.

1. Making sure that the date/time is correct. I always check each data file to make sure that the start and end times look correct. I do this by cross-referencing the RFID data with my field notes where I have noted when I swiped the test tag at the beginning and end of deployment (see Field Protocol notes above). If the date/times are off, then I can use the field notes to figure out how offset the date/times are and correct them. To do this, I usually import the data in to excel (when you do this, you will have to use text-to-columns function to convert the data into appropriate columns), create a new column to note the difference between the real time and data time, and then create an equation to do the conversion. If your date/times are always correct and you don’t have to do this conversion… good for you! You can skip this step.

2. Include the sensor ID as a column. You can actually do this within R if your sensor ID is in the name of the file–you could just include in your script a way to add the ID into your data. But since we have typically had to go through a date/time check with our data that involves importing the data in to excel anyway, I usually just do this in excel.

3. Huge annoying thing with RFID and auto-conversion in excel. There are two main glitches that I have encountered with RFID and the tendency for Excel to auto-convert numbers… (1) If you have any RFIDs that are all numbers, Excel will take out any leading zeros–e.g., “01101855555” will become “1101855555”. (2) If you have RFID that is all numbers but with the letter “E” in there somewhere, Excel will interpret that as an exponent–e.g., “011016E038” will become “1.10E+42”. This is super annoying. If you never need to use excel in any part of your workflow, you can avoid this problem. But I will demo the case when this does happen, since I suspect we are not the only one that has to deal with this.

1.2. Sample ‘cleaned’ data from one sensor

Because I go through the extra step of checking the date/time for each file and adding the sensor ID into the data prior to importing to R, this is what my raw data from one feeder looks like:

Note: You can just use the raw data from your RFID board if you do not need to do any corrections on your date/time info. However in that case, you will still want to add the siteID at some point

2. Compile RFID data across multiple sensors

Now that the data is clean, it is time to compile the data from different sites/sensors into one dataset.

2.1. Batch import data files

For this example, I have a few test data files, which are data collected from 3 different feeders over about one week.

I can tell R where the files are located and save that as a character vector.

file_locations=list.files("RFID_sample_data/RFID_testdata",pattern=".csv", full.names=T)Then, I can use an lapply() function to import all of

those files and save them as items in a list called

files.

files=lapply(file_locations, read.csv)You can check and make sure that all files have imported correctly.

One way to do that is to use the str() function to show you

the structure of the file.

str(files) #output suppressed here because it's too long.2.2. Bind rows to create compiled data

If all of your data have the same columns, you can compile the data

into one object using the bind_rows() function from the

dplyr package.

files=lapply(files, function(x) x %>% select(RFID, Feeder, Corrected_DateTime))compiled_data=bind_rows(files)Check the data

head(compiled_data)nrow(compiled_data)## [1] 6489Note: Notice that, we NEED to have the sensor ID in each of the separate files BEFORE you bind the data together. Otherwise, you will not have that info in your final compiled data.

3. Cross-reference RFIDs with banding data

At this point, I want to check and make sure that the RFID records I have in the data stream match up with my banding records. This process will also help me pick up any RFID reading errors–which are rare, but could happen. This will also allow me to build an “individual attributes” file, which describes properties of the nodes of my social network.

Here are some cases that you may need to look out for:

Remember which tags are your ‘test tags’.

Multiple RFID for same individual. This can happen if you ever need to re-band a bird. For example, this happened for us at some point when we decided that WBNU should have a larger band than we initially used. We have one case of this in the test dataset.

RFID code problems with Excel. As noted above–Excel’s auto-conversion of numbers can cause problems (e.g., removing leading zeros, interpreting “E” as exponent)

RFID reading errors. Though rare, there are instances when the RFID scanner can log a slightly wrong code. We don’t have that in this test dataset, but it exists in some of our real data. Usually, you can figure this out because these cases will involve (1) RFID codes that do not exist in your banding data, and (2) typically, those erroroneous RFID codes will only show up once in your dataset.

3.1. Create summary of RFID detections & merge with banding data

Create a summary table of RFID tags and the number of times they appear in the data.

data_count=compiled_data %>% group_by(RFID) %>% summarize(n=n())I’m importing the banding data here, and then simplifying it so that I just have the columns I might want.

band_dat=read.csv("SampleData/RFID_sample_data/allbirds_test.csv")

band_dat_trim=band_dat %>% select(RFID_error, RFID_as_character, BAND_NUMBER, SPECIES, SEX)Note: How I deal with Excel misreading my RFID

Notice here something I’ve done with my banding data…

I actually have two columns for RFID. This is because of a problem with RFID & Excel that I mention earlier in the document: Excel removes leading zeros from numerics, and also interprets “E” as “exponent”. I’ve tried different ways to avoid this problem, but I realized after a while that, rather than trying really hard to avoid saving any file in Excel ever, it might just be better to acknowledge that this might happen and prepare for it. So I’ve just set up two columns to ensure that I can make these conversions:

“RFID_error” is what Excel converts my RFID data to when it auto-converts numerics.

“RFID_as_character” is the true RFID code, but with an underscore (“_“) at the end to ensure that it is always interpreted as a character.

band_dat_trimI can merge the summary table with the trimmed banding data to see what birds I have in the data here.

id_confirm=left_join(data_count, band_dat_trim, by=join_by("RFID"=="RFID_error"))

id_confirmI can flip through the data and see that all of the RFIDs, including the one that is screwed up (“1.10E+42”) can be matched to a band ID (it’s the last record in this dataset).

3.2. Add the test tag to the data

There is one other problem in this data, which is that one RFID–“011016F118”–does not match up with a band number. This is actually because this tag is one that was used as the test tag that was swiped at the beginning and end of each deployment.

So let’s put that in the dataset here.

test_tag="011016F118"

id_confirm$BAND_NUMBER[which(id_confirm$RFID==test_tag)]="test tag"

id_confirm3.3. Check for duplicated band numbers

In some cases, you might have individuals that were assigned different RFID tags. This happened to us when we decided that we should change the band size that we use for one of the species (White-breasted Nuthatch). This meant removing the old RFID tag and replacing it with a new one for some individual. One such individual appears here–“282189742”.

You can see this if we create a table of the number of times a

particular BAND_NUMBER shows up in this id_confirm

dataframe:

id_confirm %>% group_by(BAND_NUMBER) %>% summarize(n=n())We will leave the data like this because we ultimately want to have both of those RFID codes for that individual, but this will be good to know downstream.

This will be useful later for the social network data.

4. Detect “gathering events” using Gaussian Mixture Models

A key step for using RFID data to create social networks is to figure out a way to define a “flock” or “group” from a temporal data stream. That is: given that we just have data of detections of RFID tags scanned at several locations, how do we determine what is a “flock”? A clever solution was provided by a series of papers by Psorakis et al. (2012, 2015):

1.Psorakis I, Roberts SJ, Rezek I, Sheldon BC. (2012) Inferring social network structure in ecological systems from spatio-temporal data streams. Journal of The Royal Society Interface. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2012.0223

2.Psorakis I, Voelkl B, Garroway CJ, Radersma R, Aplin LM, Crates RA, et al. (2015) Inferring social structure from temporal data. Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 69(5):857–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-015-1906-0

The solution involves using a machine learning algorithm to detect “gathering events”–i.e., bursts of activity at the feeder, as detected by the temporal patterns of RFID detections. Using this method, we let the rhythm of feeder visitations tell us what is a ‘group’.

This method improves on the alternative, which would be to simply set an arbitrary time window, and assign birds that show up within such time windows to be part of the same flock (i.e., saying “birds that come to the feeder within 5 minutes of each other are part of the same flock”).

The machine learning algorithm, called “Gaussian Mixture Model” can implemented with a function in the package asnipe.

4.1. Prepare the data

datastream=compiled_data %>%

select(RFID, Feeder, Corrected_DateTime) %>%

left_join(., id_confirm %>% select(RFID, BAND_NUMBER)) %>%

filter(BAND_NUMBER!="test tag") %>%

mutate(datetime=mdy_hms(Corrected_DateTime)) %>%

mutate(time_num=as.numeric(datetime)) %>%

select(BAND_NUMBER, Feeder, datetime, time_num)## Joining with `by = join_by(RFID)`head(datastream)4.2. Set up the a global set of IDs

The gmmevents() function has the option to enter all

possible IDs. I highly recommend using this option if you can. What this

will do is to produce a result matrix that includes all of these IDs,

even if some individuals were not observed during the particular time

period you are looking at. This makes the downstream process much

easier.

I would do this by using the individual attributes data we created

above (id_confirm). We will do two things though:

- filter out the test tag

- just get the unique numbers because remember we have one individual with two RFID codes.

all_ids=id_confirm %>%

filter(BAND_NUMBER!="test tag") %>% #remove the test tag

pull(BAND_NUMBER) %>% #get just the band number as a vector

unique() #just get the unique numbers

all_ids## [1] "282189720" "281132695" "281132698" "282189717" "287059143" "286024582"

## [7] "287059144" "282189719" "282189742" "271117648" "141222316" "271117651"

## [13] "141222421" "287059151" "287058933" "287058934" "282189746" "282189744"

## [19] "282189740" "282189748" "271117652" "282189737" "282189738" "282189718"

## [25] "282189728" "282189755" "287058931"4.3. Divide the dataset into days

It is best if you can divide up the data into manageable pieces of time windows. It will help with running the code, and I think it will also reduce the chances of having errors in the Gaussian Mixture Model. This is what they suggest in the original Psorakis et al. (2012) paper. For diurnal birds, separating the data into each day makes biological sense, since the focal animals will not be visiting the feeders during the night.

Let’s set up the dates that we will use. In our test data, we have at least some data from each feeder on 12/06/21 to 12/14/21, so let’s set those as our dates to use:

use_dates=dates.to.use=seq(ymd("2021-12-06"), ymd("2021-12-14"),1)

use_dates## [1] "2021-12-06" "2021-12-07" "2021-12-08" "2021-12-09" "2021-12-10"

## [6] "2021-12-11" "2021-12-12" "2021-12-13" "2021-12-14"We are going to run our machine learning algorithm for each day’s data separately. We will save the outputs into a folder called “gmm_daily”. To do this, we need to create that folder, so…

If it doens’t exist already, create a “gmm_daily” folder within your data folder. (If it already exists, do nothing).

if(dir.exists("RFID_sample_data/gmm_daily/")==F) dir.create("RFID_sample_data/gmm_daily/")4.4. Try running GMM for one day

Because RFID data can be very large and the gmmevents()

function can take a while, let’s try running the function on one day’s

data. But we will go ahead and structure this as a for-loop so that

it’ll be easier to expand it to multiple days.

#test with one date

for(i in 1){

data1=datastream%>% filter(date(datetime)==use_dates[i])

gmm_out=gmmevents(time=data1$time_num, identity=data1$BAND_NUMBER, location=data1$Feeder, global_ids = all_ids)

save(gmm_out, file=paste("RFID_sample_data/gmm_daily/","gmm_", use_dates[i], ".rdata", sep=""))

}You should now see a file called “gmm_2021-12-06.rdata” in your “gmm_daily” folder.

4.5. Now test the code for multiple days

If everything goes smoothly for one day, try it with a few days by allowing “i” to be a range of numbers. Then, once that is all good, you can run it for all days.

But this can take a while, so depending on the size of your data set. So you can always run it in chunks of dates.

Here, I’m running it for all dates because I have restricted my dataset to only a few days and a few feeders.

#test with all dates

for(i in 1:length(use_dates)){

data1=datastream%>% filter(date(datetime)==use_dates[i])

gmm_out=gmmevents(time=data1$time_num, identity=data1$BAND_NUMBER, location=data1$Feeder, global_ids = all_ids)

save(gmm_out, file=paste("RFID_sample_data/gmm_daily/","gmm_", use_dates[i], ".rdata", sep=""))

}4.6. BONUS: Run it in parallel

This Gaussian Mixture Model routine can be run much more efficiently by using parallel computing. All modern computers are capable of parallel computing across multiple ‘cores’.

Load the packages you need for running this routine.

library(doParallel)

library(foreach)

library(parallel)You can see how many cores you have on your computer using the

detectCores() function from the parallel

package.

detectCores()## [1] 8Run the gmmevents() routine using parallel computing by setting up a

‘cluster’ using the registerDoParallel() function and then

using the foreach() function.

numCores=2 #change to number of cores you have on your computer-1

registerDoParallel(numCores)

foreach(i = 1:length(use_dates)) %dopar% {

data1=datastream%>% filter(date(datetime)==use_dates[i])

gmm_out=gmmevents(data1$time_num, data1$BAND_NUMBER, data1$Feeder, global_ids=all_ids)

save(gmm_out, file=paste("RFID_sample_data/gmm_daily/","gmm_", use_dates[i], ".rdata", sep=""))

}5. Creating networks from outputs of GMM events model

Load all of the gmm_daily files. Add the names of the files so we don’t lose track

Note: this will only run if you’ve already run the

gmmevents() routine above

gmm_filename_full=list.files("SampleData/RFID_sample_data/gmm_daily", full.names = T)

gmm_filename_short=list.files("SampleData/RFID_sample_data/gmm_daily", full.names = F)

gmm_list=list()

for(i in 1:length(gmm_filename_full)){

load(gmm_filename_full[[i]])

gmm_list[[i]]=gmm_out

gmm_list[[i]]$name=gmm_filename_short[i]

}The network is going to be constructed from the Group-by-Individual matrix (GBI). Here, “groups” are the gathering events detected by the Gaussian Mixture Model. The GBI lists the groups along the rows and individual IDs along the columns. The cells are 1 if that bird was detected in that group, and 0 if not.

The GBIs are part of the output of the gmmevents()

function and can be called by using $gbi. Here, we will make a list of

the GBIs from all days, then “bind” these matrices by rows. In essence,

we are stitching together the Group-by-Individual matrices from each day

so that the rows have all groups detected across all feeders in all

days. Note: We can only do this if you have used the global_ids

option in the gmmevents() function so that all possible

individuals are listed on the columns for every day.

gbi.list=lapply(gmm_list, function(x) x$gbi)

all.gbi=do.call("rbind", gbi.list)Now we have one global group-by-individual matrix. Now we are going

to use the get_network() function from the asnipe

package to make an adjacency matrix–i.e., a square matrix in which both

rows and columns are individuals, and the cell values reflect the

association index. The get_network() function uses the

Simple Ratio Index as the default.

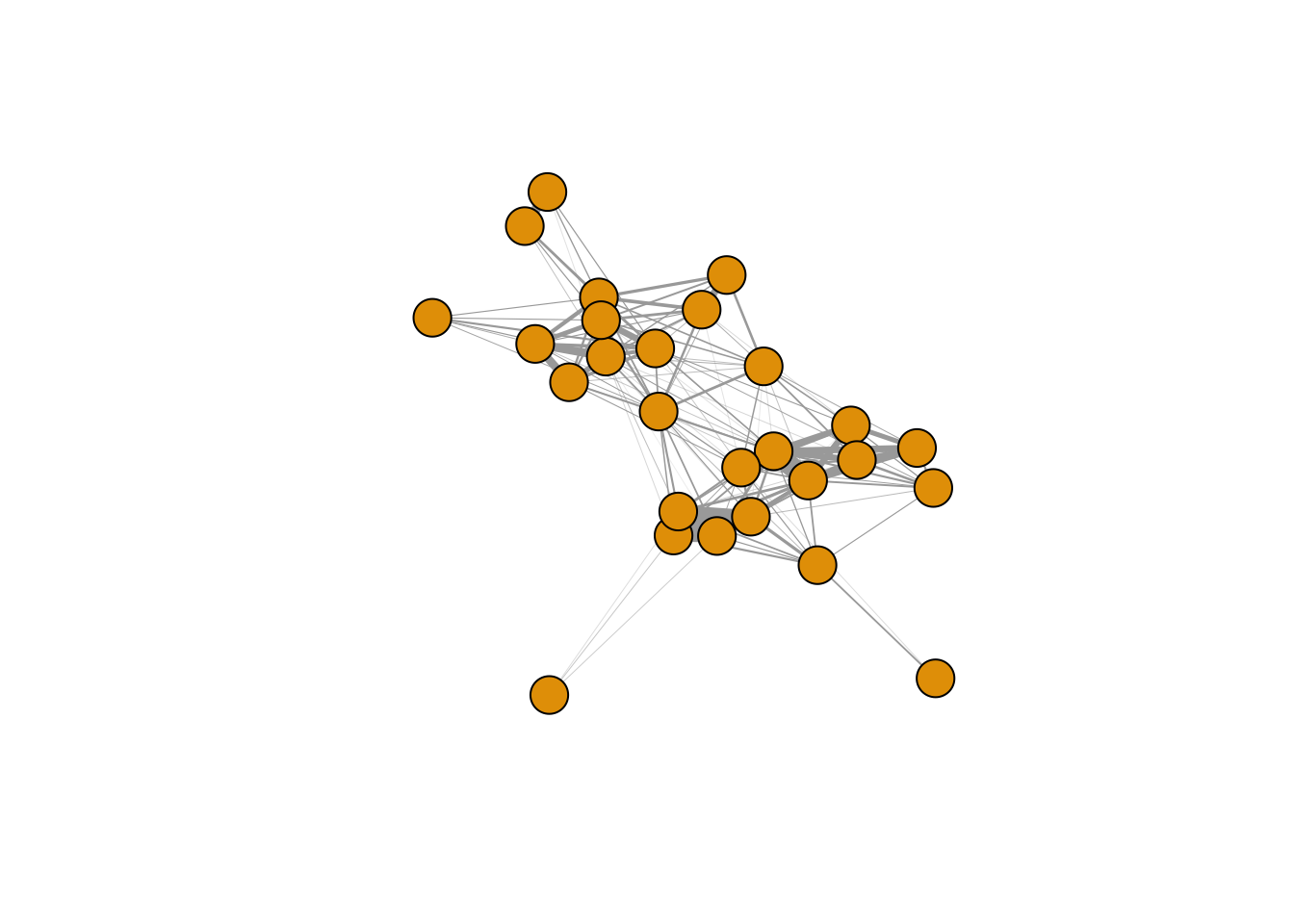

adj=get_network(all.gbi)## Generating 27 x 27 matrixFinally, we take this adjacency matrix and convert this into an

igraph object using graph_from_adjacency_matrix().

g=graph_from_adjacency_matrix(adj, mode="undirected", weighted=T)Now we can plot the network. Here, I’m going to suppress the node labels (because it makes the network hard to read), and make the edge widths proportional to their weight (but multiply by a constant so that it looks nice).

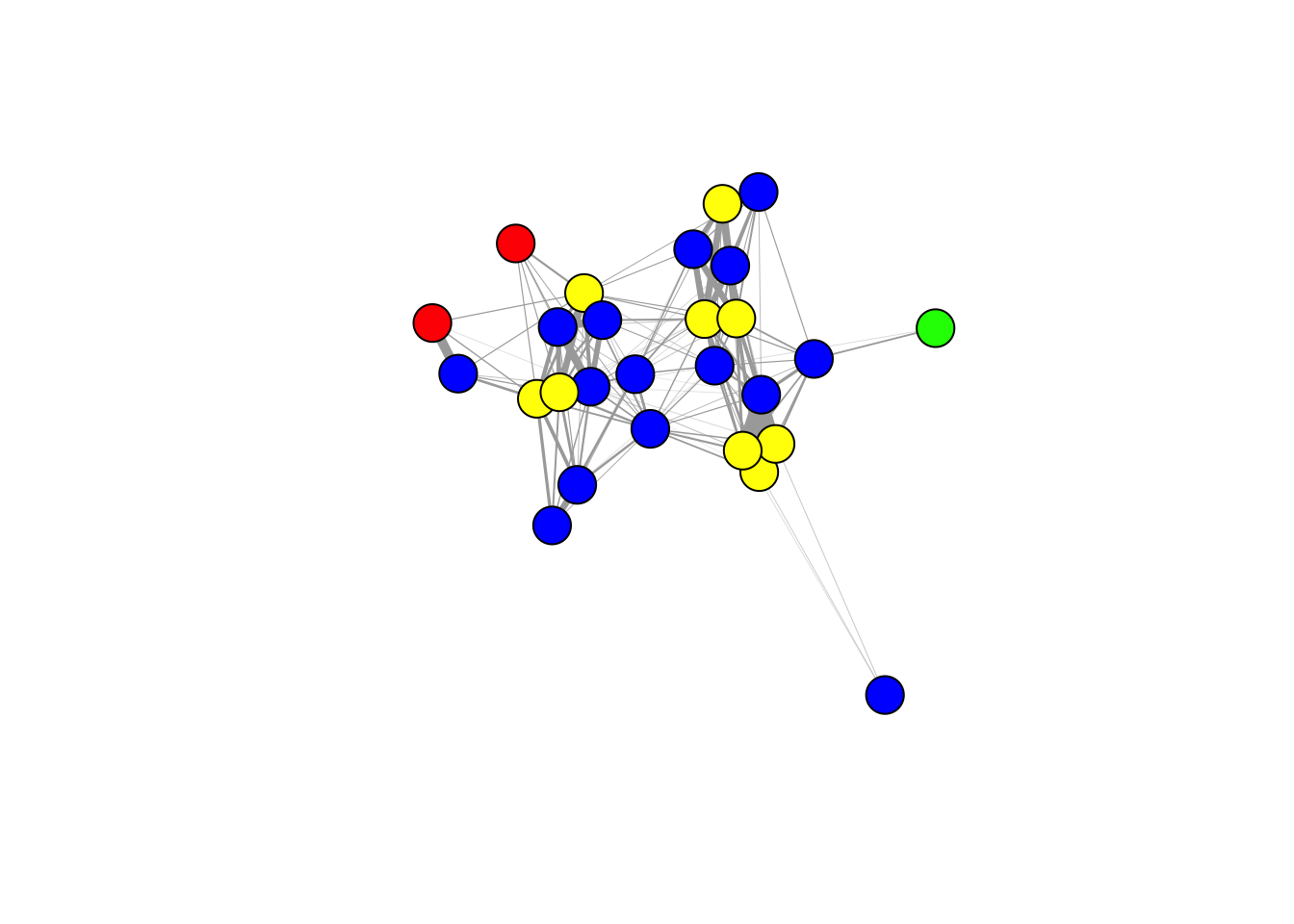

plot(g, vertex.label="", edge.width=E(g)$weight*20)

Let’s add some node attributes. Here, I’m going to first add species as a node attribute.

In igraph, node (or vertex) attributes are denoted as

“V(name_of_graph_object)$…”. So if we want the name of all vertices

(i.e., band number) in graph g, then we can use:

V(g)$name## [1] "282189720" "281132695" "281132698" "282189717" "287059143" "286024582"

## [7] "287059144" "282189719" "282189742" "271117648" "141222316" "271117651"

## [13] "141222421" "287059151" "287058933" "287058934" "282189746" "282189744"

## [19] "282189740" "282189748" "271117652" "282189737" "282189738" "282189718"

## [25] "282189728" "282189755" "287058931"Using the same logic, we can assign new node attributes. For example, let’s add species to the nodes. I’ll do this by using a match function to look up the band number of the nodes in the individual attributes data, then return the species of that individual.

V(g)$spp=as.character(id_confirm$SPECIES[match(V(g)$name, id_confirm$BAND_NUMBER)])

V(g)$spp## [1] "WBNU" "BCCH" "BCCH" "WBNU" "BCCH" "BCCH" "BCCH" "WBNU" "WBNU" "WBNU"

## [11] "RBWO" "WBNU" "RBWO" "BCCH" "BCCH" "BCCH" "WBNU" "WBNU" "WBNU" "WBNU"

## [21] "DOWO" "WBNU" "WBNU" "WBNU" "WBNU" "WBNU" "BCCH"Now, I’ll create a simple matrix to act as a conversion table between species ID and color. Then, we’ll use that to assign a color to the nodes in the network.

spp_colors=matrix(c("BCCH", "DOWO", "RBWO", "WBNU", "yellow", "green", "red", "blue"), ncol=2)

V(g)$spp_col=spp_colors[match(V(g)$spp, spp_colors[,1]),2]Then, we can now use that node attribute to color the nodes in the plot

plot(g, vertex.label="", edge.width=E(g)$weight*20, vertex.color=V(g)$spp_col)